Photos by Jack A. Waldron

It is quite amazing when you think back to your earliest academic experiences as a child, dreaming through the lavishly painted pictures of the bible stories, or, "there once was a spider who swallowed a fly, why he swallowed the fly I don't know why, perhaps he'll die . . . ", and then, there is King Midas and his golden touch, or the Gordion Knot, which Alexander the Great powerfully and impatiently slashed without reverence for its artistry. The later of these most famous myths grew from this ancient city, Gordion.

The tumulus of King Midas can be seen jutting into the sky on the horizon in the photo above. The sign pictured below sits at the Phyrgian Gate entrance.

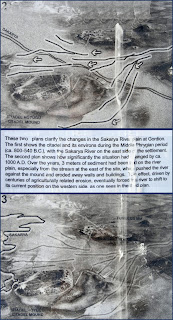

The foot print-like outline in the photos above and below, is the early city wall surrounding Gordion. The large red half-circle in the upper right of the photo above is the Tumulus of King Midas. There will be a second blog post which will cover King Midas, the site Archaeological Museum and the antiquities in the area around the museum.

Gordion is situated on lofty plain on the northern side of the hills separating it from the modern city of Polatli to the southeast, where I based myself, hence the reason I am not carrying all of my panniers. The Sakaraya River (ancient name, Sangarios) flows past Gordion toward the Black Sea.

Gordion sits on a major ancient highway that brought trade from both the distant east and west. During Persian control of Anatolia the trade route connected the capital city of Persia, Susa, with Aegean coast, covering some 2500 kilometers. The probable reason in fortifying this site was that the Sangarios River was easily crossed at this location.

The ramp leading up to the Phrygian Gate was 6 meters wide with tall towers on either side, which allowed the defenders of the city to thwart attacks on the gate. As can be seen in the photo above, the ramp climbed to a terrace on which the gate was located. Excavations and restoration of the gate are ongoing (pictured above and below).

Pictured above and below, a view of the inside of the Phrygian Gate from the defensive wall on the opposite side of the citadel. Again, the Tumulus of King Midas can be seen in the distance.

The greater population lived and worked out on the plain surrounding the city, mainly engaged in farming activities and various productions that really differ very little when compared to the population that inhabits the same area today.

The citadel is dominated by the palace and its megarons, which was a series of large rectangular rooms that supported numerous activities, from garment production to cooking, or state affairs to recreation.

Pictured above, a view of the Phrygian Gate from the north defensive wall. Some remnants of the earlier gate and lower defensive wall can be seen in the use of colored stone. The newer gate and citadel walls were heightend 4-5 meters.

Pictured below, a section of the middle Phrygian Gate complex featuring the use of colored stone. The main entrance of the Phrygian Gate can be seen in the left of the photo.

Pictured below, a distant view of the Phrygian Gate from northeast section of the defensive wall. One can see the great advantage of the defenders of the city by having such a long protruding wall out from either side of the gate.

Just inside and across from the main gate on a long terrace are the stone foundations for the mud brick walls of the megarons (pictured below). Similar to the buildings of the Hittites, Phrygian construction used stone foundations to support mud brick walls.

Megaron 2 contained the earliest to date example of pebble mosaic (pictured above in situ 1956, and below today), now located at the museum in front of the Midas Tumulus.

As you can see in the photo below of Megaron 1 and 2, preservation of the stone base of the megaron walls is done with an earthen cap as opposed to a concrete cap is still commonly seen at many ancient sites.

Concrete traps moisture within the stone, which does great damage as it expands and contracts according to the climate conditions.

In the photo below, one can imagine mud brick walls rising on their stone bases. These halls would have served many purposes, such as food storage, reception hall for visiting dignitaries, cloth and leather production, and so on. Pictured below, the Terrace Buildings, with the methods used to preserve them pictured and described above.

Further, there are well preserved terra-cotta tiles in the museum showing the exquisite decoration that adorned these buildings (pictures below).

Serving an exact architectural function was an important aspect in these buildings, such as the gutters (pictured above), however, decorative aesthetic was also an element of refinement that displayed the wealth of a construction.

Plaques were also used to decorate or signify a given building, whether to be protected by the gods, display power and wealth, or perhaps some other purposes.

Pictured above and below, the Southern Gate of the citadel as pictured from the outside. Unfortunately, entrance into the city is forbidden for tourists as preservation of such a fragile site takes priority over individual investigation.

Leaving the Southern Gate area, I backtracked to the east of the site to view the Lower Town and Kucuk Hoyuk, which appears to have become a defensive fortress of last refuge, more easily managed than the large citadel.

Beyond myself and the sign pictured below sits the remains of the Lower Town. In the distance is Kucuk Hoyuk, which was perhaps where Lydian defenders made their last stand after coming under siege from the great Persian army of Cyrus the Great. This might make sense as the area involved was smaller, thus easier to defend by fewer hands.

*All photos and content property of Jack A. Waldron (photos may not be used without written permission)

**If you'd like to help with future postings, please feel free to support them through PATREON:

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.