Photos by Jack A. Waldron

Continuing on from the Stadium, which is where the previous post, 'Miletus: Bay of Grande Monuments Pt.1, ended, it is easy to access the massive Baths of Faustina (37°31'41.9"N 27°16'36.9"E), that are a very short distance across the Palaestra from the Stadium.

Pictured below, is the Apodyterium of the Baths of Faustina. The baths of Faustina were built between 161-180 CE, and were funded from the purse of Faustina herself. The Apodyterium was the main entry with access to both the Palaetstra and the Baths, which consisted of cubicles for changing and storing ones clothes while the exercised and/or bathed, or both.

In an unfortunate accident in the Taurus mountains of Cappadocia in 175 CE, just 30 km south of Tyana in a military camp named Halala, the matron of the baths at Miletus died in the company of her husband, Marcus Aurelius. Halala was soon declared a town by the Emperor, and was given the name, Faustinopolis. Pictured above and below is the south entrance to the Apodyterium, and as you can see, this was and remains a monumental structure. Looking through the entrance to the north, you can see the Theater rising in the distance, however, in ancient times this room would have been covered by a tall vaulted arched roof.

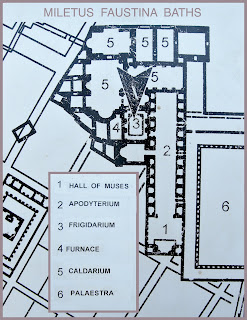

In the plan below, I began my exploration at the entrance just outside the '5' at the top right corner, which is where the photos above were taken from. I first walked through the Apodyterium to the main entrance (number '1' on the plan), which is where the Hall of Muses is located.

The Hall of Muses, the large square room seen in the left of the photo below, would have displayed statues of various figures, perhaps those of Hadrian, Faustina, and other Romans of the highest stature.

To strike a more classical theme, the Hall of Muses might have put on display statues of Hygeia, Aphrodite, Apollo or Zeus: all this in order to create an environment that reflected the desired atmosphere.

An atmosphere of health may have been conjured up when a baths patron viewed a statue of Hygeia, the goddess of health. A statue of Aphrodite displaying the sensual beauty we may desire to possess, certainly may have motivated a few baths patrons to take care of their bodies.

A Hall of Muses of a private Hellenistic or Roman villa may have had statues of Socrates, Plato and Aristotle, in order to create an environment of philosophy, letters and academics.

In the right of the illustration below, the colonnade of the Palaestra/Gymnasium, is viewed from the same vantage point as in the photo shown above, where the bases of the colonnade can still be seen. At the opposite corner of the Palaestra (from the one pictured here), is where the Palaestra meets the Stadium. An inscription on the entablature of the Palaestra propylon entrance states that both the Stadium and the Palaestra were financed by Eumenes II of Pergamon during the middle of the 2C BCE. The large square room at the left forefront of the illustration is the Hall of Muses, which is separated from the Apodyterium just beyond by a grande arched entrance.

A long rectangular Corinthian capital that once sat atop one of the entrance columns pictured in both the right and left of the photo above can be seen on the ground in the center left of the photo below.

Numerous inscriptions on benches, columns and dedicatory bases can be found within the bath complex. Pictured below, this long inscription, known as the 'Makarios Inscription', can be seen on the long rectangular Corinthian column discussed above.

The 'Makarios Inscription' translates in the following:

"In good fortune; [text missing] Makarios, ravaging, warded off battle with killers and, as he increased his renown greatly in the cities, he built a new bath in return for his Asiarchy."

"In good fortune; this is the mighty ornament of Makarios in this place, which he built for his native city in willing gratitude for its nurture; in return for his Asiarchy, he finished an esteemed reputation for the city with the generosities of his wife, Eucharia."

"In good fortune; Makarios, the second steward of labors, restored the Bath of Faustina to its ancient beauty. Tatianos, the judge, found an end of the work when he summoned the fire-wedded nymphs. He gave an ornament to the city: all are relieved from their toils as they were Faustina's by name but now our city will call you Makarios', because he was unstinting with his property and, with a proud spirit, he scraped off old age and made you new again."

Reserved bench perhaps?

Some of these may be honorary dedications to the various families that provided funds to help in the construction of the baths.

Pictured below, we have the entrance to the Caldarium rooms, or hot rooms, synonomus with caldron, that which facilitates the heating of something, in this case, the human body. There are no less than five separate Caldarium rooms in the Baths of Faustina.

Only the bare bones of the structure remain today, yet still impressive in size and scope. The walls once had purposed spaces within them that carried and circulated the heat in order to create steady temperature anywhere within the room, including the raised floor.

Furthermore, as can be seen by the fine decorative building members pictured below, the structure would have offered a similar grandness when compared to the countless neoclassical structures that are admired around the world, from Tokyo to Wall Street, Berlin to Buenos Aires.

Pictured below, you are now looking at the spectacular remains of this nearly two-thousand year old structure, and more specifically the Caldarium, with walls that still stand to around 15 meters in height.

The Caldarium rooms are large, extensive and act as a maze of sorts as you twist and turn your way through the complex (pictured above and below).

Eventually, you will find your way to the Frigidarium, where a large swimming pool greets those enter.

Lion sculptures that once adorned an ornately decorated fountain remain in situ, and at the head of the pool, Meaender, the river god (pictured below, on display at the Miletus Archaeological Museum), reclines over a once flowing spring of water.

Can you picture the patrons enjoying their reprieve from the hot summer sun just outside the bath walls, while nearby in the Apodyterium their slaves wait, guarding the clothes, scandals and what not of their masters?

After my visit to the Baths of Faustina, my next stop was the Roman Heroon III, which can be found on the city plan below, not far from the baths.

Here is a short history of Miletus, and after that, we head to the Roman Heroon III, the largest mausoleum in the city. In the future, I hope to explore the Necropolis of Miletus, which is quite distant from the city center.

The structure known as the Roman Heroon III was built during the 3C CE, and is located between the Baths of Faustina and the Bouleutarion. In the illustration below, the Roman Heroon III can be seen in the lower left hand corner of the picture, surrounded on all four sides by a portico.

The Serapeion is located off the southwest side of the South Agora, not far from the Roman Heroon III and the Baths of Faustina. The Temple of Serapis dedecated to Zeus-Serapis is dated to 3C BCE as part of the Graeco-Egyptian cult that expanded under the policies of Ptolemy I Soter.

Pictured above with the Theater and Byzantine Fortress once again rising in the distance, the Temple of Serapis is described as a basilica type structure serving the interests of the believers of Serapis, including the Egyptian traders and merchants who had close ties with, Egypt, Alexandria, and the Ptolemaic kings.

The structure was fronted with a tetra style portico of marble supported by four columns, while inside there were two aisles on either side of a main nave that was supported by two rows of ionic columns running the length of the building.

You can see the back of the portico pediment in the middle right of the photo above, near its original position on the building. The columns standing in this photo, and row of column bases four meters or so to the left in the photo, formed the two rows and the three aisles of the basilica structure. Pictured below, the front of the pediment of the marble portico sits near the position where it would have when the structure was erect.

I find it interesting that, when the term basilica is used, the image that comes to mind most often is that of a church building, and the duties performed through it. However, here we have a Hellenistic basilica structure that served its believers and organized functions for the greater polis as an extension of the governing or ruling body, and a fine example of the many societal constructs inherited from this and previous periods.

As for this particular structure, and focusing on the pediment and the chosen decorative relief at its center, images of the lighthouse of Alexandria, or the colossal statue pharos of Rhodes come to mind; for it is Helios, the god of the sun and sight, that directs the merchant marine safely into the bays of the ancient world. Now defaced, we can clearly see the aureole crown of the sun god, yet another image borrowed by believers of a later age. Further, the robe of the relief is clearly pronounced, and this was probably on purpose, because the mythical handsome beardless sun god was usually draped with a robe dyed of the royal purple.

*All photos and content property of Jack A. Waldron (photos may not be used without written permission)

**Please support my work and future postings through PATREON:

Or, make a Donation through PayPal: