Photos by Jack A. Waldron

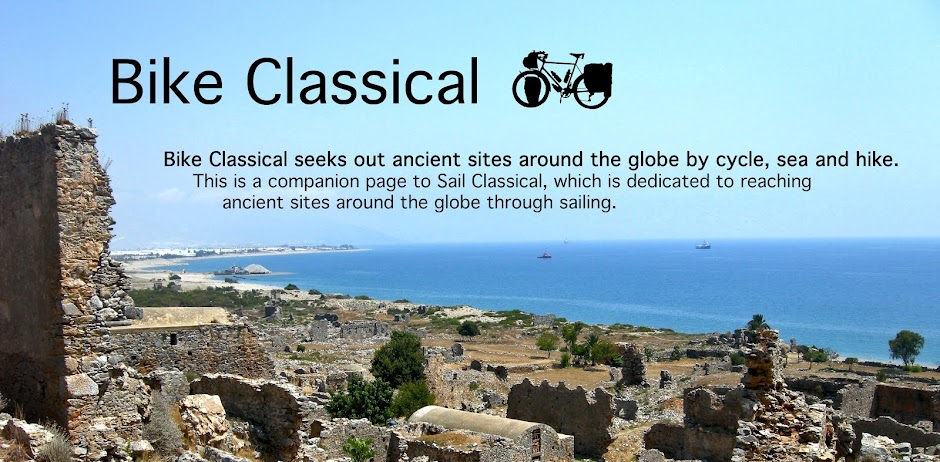

My Surly Disc Trucker did well to get me this far (pictured in the lower right corner of the photo above), but I had to walk it back to the Oretmenevi (Teacher House, or, Teacher's Hotel), because my front brake-pad got all jammed up in the caliper. This experience instilled in me even deeper, that old boy scout motto,"Be Prepared". The reasoning of why I wasn't prepared this time must be, because I only made it to Webelos, whose motto is "Do Your Best". I hadn't brought my tool kit along on my around the city tour. I will never go anywhere without it again!!

In the left of the photo, the Alaca Tomb, built in the 13C AD for Emir Cemalettin and Bin Muhammed (to be explored more deeply in Caesarea Mazaka Part 2). The southern corner of the city wall in the background of the photo above is referred to as the Yogun Burc (Intense Bastion), and is located on Talas Street, where the Roman wall of the city met the Byzantine wall.

The Yogun Burc, or Yozettinburc, is on of two bastions dating from this period (pictured above). It was built on a semi-circular plan by Izzettin Keykavas, contains two stories, each with pointed vault roofs, and was used as a government building and prison during the 13C AD. I was a bit hesitant to allow so much distance between the bike and myself, but I just had to get a shot of Yogun Burc with my cycle (pictured above)!

The other bastion was apparently built by Alaeddin Keykubad, and is known as the 'Ok Bastion'. The southern section of wall has not survived the ages, and was probably quarried for its stone blocks.

In very similar fashion to the city walls of ancient Melitene (Malatya), the gate and wall construction (pictured below) uses small square rough cut blocks, only in this case they also have a finished facade with finely smoothed blocks. This finished facade may date from a later period. As far as I saw, the city walls of Melitene were finished in square rough stone (pictured below, under the finished stone). The castle and its walls were in fact built by the Byzantines, similarly to the walls of Melitene, and around the same period. Melitene was the endpoint of the the major highway that ran southeast from Caesarea.

With evening fast approaching, and the bicycle in need of some attention, it was time to get back to the Teacher's Hotel to prepare for the next day, a visit to the Archeological Museum, and a walking/cycling tour of the ancient tombs and buildings.

Kayseri takes its name from the Roman 'Caesarea'. If you change the 'c' sound in 'Caesarea' (Koine Greek pronunciation), to the 'k' sound (Latin pronunciation), you will understand the modern day pronunciation, Kayseri. The greater area however, has a much more ancient past, that reaches back long before the Romans took control. This was a major hub of Assyrian and Hittite trade beginning around 2000 BCE.

Though I did not take the opportunity to visit Kultepe, the site of which is about 12 kilometers northeast of Kayseri, tablets found there contain the oldest written form of the Indo-European language, that record the establishment of an Assyrian colony where trade took place on the beginnings of that branch of the Silk Road, around 3000 BCE.

Kayseri, not to be confused with Kultepe, was founded by an Armenian named Mishak, and so, what became the capital city of Armenian Cappadocia would take a name based on its founder, hence, the new city was named Mazaka.

As a side note, all of the museum photos included in this post are from the Kayseri Archeological Museum (pictured above), which I highly recommend visiting the next time you're in the area.

The city would keep this name, even as a Roman province, until the 1C AD, though it was also called Eusebia, after the King of Cappadocia, Ariarathes V Eusebes (163-130 BCE). We know that Mishak predated the sarcophagus pictured above by a few hundred years, however, the founding name of the city would be buried, or put to rest (excuse the puns) during the 1C AD, when this burial box was created.

In 14 AD, Archelaus (36 BCE - 14 AD), the last vassal King of Cappadocia under the Romans, changed the name of the city to Caesarea (though the emperor Tiberius may have made this decision), as a dedication to Caesar Augustus following his death.

The remaining walls and towers that we see today are are a hodgepodge of Roman, Byzantine, Seljuk, Ottoman, and an amalgamation of modern day destruction and construction. Pictured above and below, Kayseri Castle dates back to the Roman period, and was first mentioned between 238-244 AD by Emperor Gordian III.

Like the ancient walls of the city, the castle has been modified many times over the millennia. The castle has seen ownership change many times, including under the Romans, Byzantines, Danishmends, Seljuks, Dulqadris, Karamanids, Ottomans, and Turks. Though I haven't counted them, there are 18 towers in total, and the castle includes and outer section, as well as an inner section.

The heavy traffic circling the castle and walls at very short quarters makes it a bit of a hectic walk. There are a few hidden streets that take you away from the hustle and bustle, but the ancient feel is lost a little with all the modern shops and restaurants.

The city was destroyed in the 3C AD by the army of the Sassanid King of Kings Shapur I, when he defeated Emperor Valerian I. It slowly recovered, but during the 7C AD, it was completely destroyed by the Arab general Muawiyah, and remained uninhabited for over 50 years. It again recovered under Byzantine rule, and was slowly rebuilt and refortified.

I wasn't intending to include any post Byzantine information or observations in this post, because I am saving that for Part II, but when I started walking around Hacikilic Madrassah and Mosque, well, the pre-Islamic building blocks began to stand out.

As stated above, I hadn't planned on including any post Byzantine photos in this post, and when you look at the mosque/madrassah pictured above, well, let us call it a Roman/Byzantine/Islamic mosque. Even from such a distance, we can see that this structure was built from quarried stone blocks, but as you approach, the more ancient history begins to reveal an interesting story.

There, in the wall, next to the round structure built with stone blocks cut to purpose, a section of Roman architrave, and next it, a section of Byzantine sarcophagus?

The main structure of the Hacikilic Madrassah, and later Mosque, was constructed in 1249, only 177 years after the Byzantines had lost most of Asia Minor to the Seljuk Turks as a result of their loss at Manzikert in 1071. So, the Seljuks rebuilt with the remains and rubble left to them after centuries of fighting and destruction.

As we come around to the front of the structure, we find a different story, a new story, at least for the ancient city of Caesarea. In 1067, Alp Arslan and his army captured the city, destroyed the buildings, and massacred the population. The city remained uninhabited for the next 50 years.

The Danishmendids from the north and east of Anatolia rebuilt Caesarea, or Kayseri, around 1134, and controlled it until the Seljuk Sultanate of Anatolia took it over in 1178.

This was the status quo, until the Mongols arrived in 1243, when the took the city. Most of the rebuilding of the city occurred over the following 3-4 centuries, and then in 1515, the Ottomans took the reins, and administered the future of ancient Caesarea.

I was not able to find any ancient plans of Mazaka, Caesarea, or, post Byzantine, though I will keep looking, perhaps some AI bots could help, but I think a lifetime spent in the libraries of the world would be more fruitful.

It has always been a dilemma for me, to investigate the ancient world by physically exploring it, or, study it from a few isolated locations? Was this Hacikilic Madrassah and Mosque built over an ancient Roman temple, like many Christian churches were? Or, perhaps the Islamic building was built over the Christian building, which was built over the Roman building, which was built over the Armenian temple?

Speaking of the Armenians, if you recall, Kayseri, was founded by an Armenian named Mishak, who gave the capital city of Armenian Cappadocia the name, Mazaka. Armenians have been part of this land since pre-history, with only the gods, their names, the rituals, and the mindsets simply adapting, adopting, and changing over time.

Pictured above and below is the Meryem Ana Kilisesi, or Mother Mary Church, built between 1835 and 1838 for Armenian Catholic worship, and now being restored to serve as a library, a simple stroll around this structure reveals a more ancient past.

As you can clearly make out in the photo below, stone blocks from more ancient structures were quarried for the construction of the church. And further, what seems obvious is that we are looking at a pair of scissors sandwiched between two parallel rods with stops, or caps at each end. As I have not the deep knowledge at this time to say exactly what this image depicts (I will continue to search), I do have some speculations to make.

Since I believe the majority of these stone blocks originate from the Byzantine period, though some may have come from late-Roman, or earlier, the imagery found on them reveal deep historical legacy, sometimes dark, sometimes bright, but hidden amongst the walls of cultures both past and present.

The scissor motif is an image that repeats quite often on the blocks of the walls of the Mother Mary Church, or Church of the Virgin Mary. Under the rule of Christian Rome, and the Byzantines, Caesarea (Ponti) was second as a metropolitan see only to Constantinople itself.

Between the 7C and 10C, the number of suffragan dioceses grew from 5 to 15, which included the Armenian Catholic Church, and the Melkite Catholic Church. There is a link here, between this history and the scissor motif.

I think the scissors represent tonsure, the Oriental version of which was adhered to by the Eastern churches, and consisted of shaving the entire head as a sign of humility and devotion.

Kayseri/Caesarea was a religious center for Eastern Christianity, producing numerous archbishops over the first two millennia, who were given the title protothronos, meaning "of the first see", so as a religious center, the city was only second to Constantinople.

One thing my 21st century mind has difficulty wrapping its thinking around is, what did the Armenian architects and builders have in mind when they erected this church? I mean, didn't they understand the symbolism etched into the stone blocks? Weren't they aware the antiquities they were utilizing? And, I think they may have.

Perhaps the architects and builders were setting in stone, a building that put on display the remnants of a much older Christian tradition within this land. Here, for future generations to view and on full display, a Christian tradition in this land that pre-dates the tides and currents of present beliefs. And yet, tolerance of an Armenian Christian Church to be constructed during the 19C, well, that was perhaps a reflection of the population of Kayseri at that time.

The Virgin Mary Church continued its function until WWI, followed by uses as a police station, warehouse, sport hall, and so on. As of this writing in February 2023, the building serves "cultural purposes" as a public library. The frescos and other interior structures have been restored, and the exterior remains a reminder of a past history of Kayseri.

I was truly fascinated by this building, in part because most of ancient Kayseri has been lost to fighting and destruction, and scavenging of the building blocks that date back to the hypogeum of Mazaka, which has been found, though I have not yet been able to locate. It is said to be at the center of the modern city, and I will continue to search for the exact location.

Upon my visit during June of 2017, restoration of the Virgin Mary Church was well underway. I have seen photos of the restored interior, but I look forward to seeing it in person when I return to Kayseri, as I still have not visited Kultepe.

Though these photos may appear to show that I was closer to the building than I actually was, the construction crews had already fenced out foot traffic, so, all of these pictured were shot from behind a barrier.

One has to wonder, does this Church sit on top of the ancient Roman or Greek temples that once adorned the city? Pictured below is a terracotta votive statue, such as would have been left at the temple by a devote in hopes of good fortune with gods. Is this Aphrodite and her erect son Priapus, or perhaps Phaon, who ferried her from Mytilene to Asia Minor?

I don't know where the votive statue pictured above was found, but could it have been excavated from under this church? If the site was retrieved by the Armenian Church, was it previously the site of a Byzantine church, the land of which in turn had been bequeathed by the Roman Church, that had earlier claimed the site of an ancient Roman temple, built atop a more ancient Greek temple?

Regardless, the architecture screams Neo-classical design in every aspect of its being. Further, the percentage of purpose built structural members for this specific building appear to be far and few between. If you look closely, nearly every square block is an odd fit, with little to no uniformity, excepting the decorative aspects of course.

The location of the Virgin Mary Church is in the ancient Armenian district, which was established in 1191 AD. Since we know that Mazaka (the name the city was first established under) took its moniker from the Armenian who founded the site, Mishak, then perhaps the ancient structures from its earliest history are to be found under and around this structure.

As a side note, the site was also a well known Christian pilgrimage destination, as legend has it that Gregory the Illuminator was won over by the Christian faith through his learnings at this location and, later spread the religion amongst the Armenian population.

Labelled as religious objects somewhere between the 4th and 15th centuries, I can see that the church must have been quite wealthy, a center of power and control, and an overall dominating force, religiously, politically, and militarily. The pieces pictured above, below, and throughout this post were all taken at the Kayseri Archeological Museum.

Based on the riches pictured above, I can imagine the metal object below playing a necessary security function within the religious halls of the hierarchy.

As we dig back through the history of Kayseri/Ceasarea/Mazaka, we find that the Romans were involved in these lands for a very long period of time, whether it be the Roman Republic, which dates back to before Christ, or the Eastern Roman Empire, the Byzantines, or other extensions of the Roman legacy.

Pictured above, this statue of a Roman woman was discovered in the center of Kayseri, and I think it's fair to say, there are countless hidden treasures beneath the surface of this city, including more structures and building members. Also on display at the Kayseri Archeological Museum is an extensive collection of Roman era Aquila, or, the Roman Eagle.

Some of the Aquila are massive stone sculptures, while others are simple little bronze figurines, but all of these symbols of Ancient Rome conveyed power, dedication, imperial rule, brotherhood, patriotism, romanticism, and so on. It's what one feels, when they see the flag of their country draped over the coffins of their dead soldiers.

These small bronze Aquila were probably kept in a soldiers private belongings, perhaps given to him by a loved one for good luck, or maybe he bought it himself, to keep the gods close protection. This eagle stands on a dolphin, a savior of the sea, that had a reputation of assisting drowning sailors, or others.

The Aquila pictured below is massive, and I find myself imagining this huge sculpture situated outside the entrance to the compound of the Roman Legions stationed in ancient Caesarea, who were charged with protecting the road to Comana (Cappadocia), Melitene, Samosat, Antioch On The Orontes, and beyond.

I also imagine the beautiful head of this Roman Eagle perched on display in some rich collectors house, or, perhaps a local who would like to sell it, but is afraid of getting caught by the authorities, or simply waiting to be excavated, as it may have been decapitated by an invading army during ancient times.

The eagle was a Roman military ensign, a standard, to show that a company of soldiers belonged to a group. Before the eagle, there were other ensigns, such as a clump of straw attached to the head of a spear, and later, each legion would have its individual ensign, or standard. But, the eagle, or Aquila, would be prolific throughout the Roman Empire.

The eagle remained a symbol of Rome, the Empire, and all of the other cultural aspects attached to it, well into the Byzantine period, which may explain why there are so many Aquila to be found in and around Kayseri.

Pictured above, with its head reattached, the relief of this eagle is a bit on the rough side, and though lacking any descriptive information, it may date from a very early period, perhaps of the Roman Republic.

Pictured above and below, yet more headless eagles used as yard ornamentation outside the Kayseri Archeological Museum, only these specimens have a fine standard of relief, and may date from later periods than the Aquila previously described.

Further, the talons of the eagle pictured above appear to be clutching something, and may very well be a bundle of hay or ferns, which like the straw attached to the end or top of the spear, represents the company, the group, or as the Romans referred to them, the 'maniple'.

Pictured in the background of the photo above, another Aquila in the form of a bronze figurine. The figurines in the foreground are of animals on square alters, who sacrifice to the gods should bring good favor from them, much like a Christian carries a cross.

Perhaps the bronze figurine goat pictured above was a toy for a child, or could it have been a goat that an adult carried on his/her person, always ready with a sacrificial animal at hand. Below, the reoccurring theme of the boy saved by a dolphin, a good luck charm to be sure.

Pictured below, the god of healing, Asclepius, holding a staff of entwined serpents representation in his left hand. In his right, a bag of medicinal magic? But, I also see a horn on top of his head, with sea shells adorning the sides of his crown, which is more akin to the Horns of Ammon, representing the East and West of Earth.

I see the same depiction below, Ammon. In more ancient, the Egyptian deity Ammon would be depicted with rams horns, but over time these were also associated with the fossil shells of snails and cephalopods. These shells can be seen on the sides of the head.

Alexander the Great was depicted on Hellenic coinage in the same manner, as he was the conqueror of East and West, and was declared the "Son of Ammon". Further, the Quran refers to Alexander the Great as "Dhu al-Qarnayn" (The Two-Horned One).

The figurine below depicts Sol, or Helios, the personification of the sun, and along with Luna, the moon goddess, they represent the physical world, as opposed to the metaphysical world of myth.

Finally, we have a figurine of Pan, who like Sol, or Helios, is a Proto-Indo-European god dating back to beginnings of western mythology. Pan is associated with the homeland, its fields and groves, the fertility of spring, and the innate prodding the drives reproduction.

From birth to death, the ways in which humans cope (if we can use that term) with such a stark reality, are numerous indeed. But, in the end, death comes, and those with riches often invest in a false extension of life, as I am doing with this blog, hoping that I'll be remembered for my travels, my passions, my lust for life, long after I am gone.

How this Roman tomb has survived till this day I have no idea. Perhaps it was more valuable as a store house than for its building blocks. Interestingly, this tomb has no name on its signage.

However, if you search for Garipler on Google Maps, this tomb is located and pictured! And further, since this tomb is located in the Garipler area of Kayseri, then I will assume this is the tomb by the same name.

Pictured above and below, a polished stone hollowed out to be a box of some sort? A talisman? Or maybe to carry a prayer, a religious relic, holy water, some snuff for the owner?

Pictured below, a polished shell that may have been half of a shell box, and which was also found at the Garipler Tumulus.

And let's admit, this 2-3C AD tomb is quite attractive, and from the bamblings on the sign, I can deduct that the tomb was reused during the Islamic period, much like Greek and Roman temples were often converted into churches.

I do suspect that the tomb may have been damaged at some point, either out of the destructive practices of invading armies, or the destructive practices of the gods in the form of an earthquake, or maybe the new tenant needed a large hole in the wall in order to insert a large sarcophagus? You can see that four of the architrave blocks above the green door opening d not match the architrave that continues around the structure.

In such a tomb, I can easily imagine a sarcophagus such as the 1C AD Roman specimen pictured below. I have to admit, that in all of the museums I have visited, these type sarcophagi are rare. In most instances, the metal was melted down to serve the living long long ago.

The unfortunate thing about ancient Mazaka, Caesarea, and so on, is that the city was destroyed so completely on several occasions in ancient times, that there is often little account for where the museum pieces originated from (such is the case for the sarcophagi at the Kayseri Archeological Museum), or perhaps, the curators see no reason to bother the lay public with such details?

Actually, the Kayseri Archeological Museum displays need a lot of upgrading, especially when compared with many many other museums around Turkey. Now that Kayseri has become a tourist gateway into Cappadocia, perhaps they'll consider spending some money on the museum.

Pictured above is a computer screenshot I took of Bestepeler, which translates into English as, Five Hills. If you look beyond the car park and trees, you will see a mound, which is actually the remains of a Roman tumulus. This hilltop tumulus reminds me of the tumuli high above ancient Comana Chryse (Cappadocia) in Tufanbeyli, very near Kayseri to the east, and along the same ancient road to Miletene as previously mentioned, only there you cannot drive your car to them!

The gold objects pictured above and below were recovered from the Bedtepeler Tumulus, and when you see these examples of the riches that can be found under such burial mounds, you begin to understand why locals have destroyed so many of them.

The urn pictured below (I am assuming it is an urn, though it may simply be an elaborate water vessel), was amongst the objects stated to be from the Bestepeler Tumulus, has a most unusual handle, which I imagine made it easier to carry when full, as one could slip it over a shoulder.

The Kayseri Archeological Museum has some superbly sculpted sarcophagi on display, and they are labelled loosely as, "From Mazaka".

Pictured above, what looks like the corner of a small sarcophagus. Again, I wish there was more detailed information on exactly where these were found, which may in return offer a deeper story.

In the top of the lid (pictured below), a curious addition to it was a relief with small holes that allow access to the inner chamber. I assumed these were breathing holes, but, could a liquid have been injected into the box? Perhaps a fragrance, or a preservative? Interesting.

This is a sarcophagus made for a baby, or child, and it is one of the more ornately carved sarcophagi that I have seen that was intended for a child, and in marble as well.

One of the most famous sarcophagi on display at the Kayseri Archeological Museum is the Twelve Labors Of Hercules Sarcophagus. Pictured below, the signboard listing the twelve labors of Hercules, which I will allow you (the reader) to go through the photos uninhibited with my banter to find them out for yourselves.

Starting with the first photo below, I circle the sarcophagus to the right from the left, until I have documented all sides.

Pictured above, entrance to the temple heroon. Pictured below just off the corner, No.1, Fight with the Nemean Lion.

No.2 (second relief), Slaughter of the dragon Hydria.

No.3 (center), Fight with the Erymantos Boar.

No.4 (second from right), Catch of the Kyreneian Deer.

No.5 (Corner, right), Birds of the Stympholos Lake.

No.6 (left, under pediment), Cleaning of the Augean Stables.

No.7 (right, under pediment), Catch of the Cretan Bull.

No.8 (corner), Horses of the Diomede.

No.9, Fight with Hippolyta, Queen of the Amazons.

No.10, Bring of the Geryon Oxen to Euryheus.

No.11, Getting the Golden Apples of the Hesperides.

No.12, Bringing Cerberus from the Lower World. Pictured below, one of the many sarcophagi decorating the museum courtyard. The relief of this particular piece caught my eye, Medusa in a scene that appears to depict her being crowned victor by twin Nike, the goddess of victory.

Another interesting sarcophagi that stood out was the Zincidere piece (pictured below), with its robust and powerful images of bulls and garlands, as well as its temple pediment, which features a soldiers shield. This certainly must have been sculpted for a member of the military.

Zincidere is a village southeast of Kayseri, though it has basically become a suburb of the city. I couldn't find any traces of its ancient past, nor glory.

Among the numerous sarcophagi in the courtyard, there are some other very interesting pieces, such as the tall sculpted monument pictured below. I suspect that this is a dedicatory base, that may have had a statue placed on its top?

Jewelry such as the piece pictured above, perhaps a favorite of the deceased, or the rings pictured below, with etched reliefs, may have been found with or on the dead in their burial tombs, sarcophagi, or in urns.

Maybe these pieces of gold jewelry were simply lost by their owner while on a stroll through the city. I myself have a whole collection of jewelry pieces, though mine are modern, cheap, and of no value.

Like today, whether rich or poor, most people like to display fashionable jewelry, such as the ornate and probably expensive golden ring pictured below, or of lesser expense, a pair of simple earrings.

The less rich may have been interred in terracotta sarcophagi, such as those pictured below, which are on display at the Kayseri Archeological Museum. I'm sure there is a map somewhere at the museum, or at a university, that shows the location of the Caesarea/Mazaka necropolis, but I have not been able to find it.

They did the job well, but lack the vanity, ego, and sense of self-importance that the massive ornately sculpted marble sarcophagi display. I am curious about the small access hole in the lids.

The sarcophagus picture below appears to have imitation iron straps, that I imagine were bolted into and wrapped around a wooden box? If true, then there may be some real life examples of such wooden and iron sarcophagi, no?

Or, perhaps this is simply design serving up a non-reality, in order to pose wanton reality, of security? Perhaps the box is not wood, but more iron, a poor mans' display of strength, power, wealth, status?

Were these sarcophagi not buried in the earth? Were these large boxes placed on tomb beds? We have seen many tombs with beds jutting out from the walls, so were these sarcophagi laid on top of them, or, perhaps in niches in a catacomb?

The holes appear to be access points, but to what purpose? There are even latches, or strap rings, that would allow the holes to be opened. Were these intended to offer the dead some libations or food during communal visits?

In the sarcophagi pictured above and below, we would have been able to get a full view of the decomposing head and face. Of course, the tomb that housed these sarcophagi would have been very dark, and certainly would have required some lighting, otherwise I would not be able to see uncle Joe's sunken face.

Bring in the lamps!

Oil lamps allowed humans to extend their workdays, private passions, personal navigation of the buildings, and so on. When I was a child, and the electricity was out, my mother was at the ready with kerosene lamps.

When I was 9 or 10 years old, I stole a red glassed kerosene lamp from a city road work site in Detroit. The point being, electric light have been in our lives for an extremely short period of time. These oil lamps were the standard for thousands of years. People are still alive who used oil lamps on a daily basis.

Is that the head of Medusa pictured on the lamp above, perhaps meant to keep the evil darkness at bay, while pictured below, revelers at a Dionysian event dance in the flashes of light from the burning flame?

Unlike the demise of oil lamps, pottery is still used n nearly every household around the planet. Professor Zinman, the head of my philosophy department at James Madison College once asked me, "Why do [I] think people were so different thousands of years ago?"

The relief in these pieces of pottery are very telling of the culture and place of use. A drinking cup, probably for wine, shows Eros playing a harp for suggestive accompaniment.

I've included the photos of these Roman era storage vessels in this post, because who knows, perhaps they were found within the Roman baths complex?

Surly, there must have been more than one Roman bath in Kayseri? Pictured below, the rarely visited Roman baths complex, which is located not too distant from the castle.

Even the modern fence looks ancient, as this site has little to offer in terms of informational value, I mean, to the trained eye it's a bonanza, but for the tourist whose destination is Cappadocia?

I could have easily hopped this fence for a closer look, and I honestly don't think any passerby would have questioned the move, but, I am a shy guy, and not wanting to draw any possible attention to myself, I snapped my photos from afar.

I have visited and explored a great many Roman baths, from the Diocletian baths in Rome, to the Roman baths in Ankara, Turkey, and many more, and even the smallest baths have some sort of sign board to let the visitor understand the layout of this particular bath site. Not here.

Not even the Kayseri Archeological Museum offers any site plan or basic information of the Caesarea Baths, which I found disappointing, and left wanting. I mean, obviously there is Caldarium, Tepidarium, and Frigidarium, and so on. But, where? Where is the entrance? I could spend a lot of precious time trying to figure these things out!

And still, I return, again and again, because I am addicted to these ancient sites. They amaze me in their ruinous state, the strength of their structures, their staying power.

And so I circle around these passageways as if I were headed for the hot room, leaving my troubles behind for a dip in the warm pools of the past, surrounded by the echos of bouncing business planning the next construction, poem, or assassination.

There!! An ugly high rise structure built to collapse, while this bath has kept its base structure intact for almost two-thousand years. Why? How? The answer, because it was useful, at least to some.

After it lost its use as a bath, it became a shelter for poor families, then apartments for those in need. It was claimed by some as personal property, while others just passed through. Perhaps it was a barracks for a time, or a bordello? Maybe a hospital, or a last refuge from an invading army?

Pictured below, a goddess relief found in Saraycik, which is located on the western edge of Kayseri. To me, it looks Byzantine, so I'm not sure why the museum used the term "goddess", which implies pre-Christian. No doubt, it truly is a work of art, as I see it. As for Saraycik, there is little of the ancient world to be seen there these days, and perhaps there is more to be discovered unground, but that applies to nearly everywhere in Turkey. What a magic land!

*All photos and content property of Jack A. Waldron (photos may not be used without written permission)

**If you'd like to help with future postings, please feel free to support them through PATREON: