Photos by Jack A. Waldron

A bicycle is definitely thee way to explore Kayseri, aka ancient Caesarea, or ancient Eusebia at the Argaeus (as it was called for a short time, being named after the King of Cappadocia 163-130 BC), or ancient Mazaka (named after the site founder Mishak of Armenia), which was its first name. Of course there is the much more ancient site of Kultepe, which is located about 12 kilometers northeast of Kayseri, which I will write about in the future. I'm going to try and work back through history with this post, so we'll begin with the 14C AD tomb named Doner, and slowly work our way back in time.

The signage that accompanies these tombs is sometimes incorrect, so let's begin with Doner Tomb, which has some misleading signage (Pictured above and below). First of all, most signage at the majority of the tomb tells us little of the history, and that of the Doner Tomb is no different. Also, the history that is provided is sometimes different from the reality. I guess this is simply due to a lack of deep research by the sign making department?

Apparently, the Doner structure was built in 1276 (so, not the 14C as stated on the sign at the site, but the 13C, according to other sources), and was constructed for the daughter of Alaeddin Keykubad I, the Anatolian Seljuk Sultan from 1220 to 1237, and one of the most famous characters in post-Byzantine Anatolian history, besides Ataturk, of course.

The Doner Tomb is one of the more elaborately decorated Seljuk era quadratic pedestal base structures in Kayseri, and though we do know for whom it was built, the reliefs can also tell us a lot. The Two Headed Eagle and Leopard/Lion imagery is also important symbolism that can be found in different and more ancient cultures. Kybele was usually depicted with lions flanking her throne, them being sat on either side of her image. Kybele was also depicted under a Tree Of Life in more ancient reliefs, and here we also have what appears to be a Tree Of Life.

I find the Tree Of Life imagery quite interesting, because this harkens back to much more ancient times in Anatolia, in particular, a number of Phrygian Kybele monuments, where the Tree Of Life relief plays an important role in their mythology, or religion.

Alaeddins' daughter was name Shah Cihan Hatun, and the tomb can (and is) also referred to as the Shah Cihan Hatun Tomb, though not on the signage. There are twelve sides to this tomb, which are decorated with geometric relief and various types of vegetation. Reliefs above the door also include two winged leopard figures with human heads. Again, I can't help but be reminded of the Anatolian mother goddess, Kybele. Pictured below, my bicycle outside the gate of the Ali Cafer Tomb, 14C AD.

This tomb dedicated to Ali Chafer was constructed under the Eretna principality, which was founded by Alaeddin Eretna, who was Uyghur in origin, and is entombed at the Kosk Madrasa, which unfortunately I did not visit. This may shed some light into the Turkish support of Uyghurs in modern times.

According to sources, Ali Cafer was one of Alaeddins' three sons, who was involved in a power struggle with his brother Mehmed following their fathers' death.

Ali Cafer did eventually take the throne after a substantial amount of Machiavellian maneuvering by various parties. Ali was then dethroned by Mehmed after Cafers' army was defeated at the Battle of Yalnizgoz in April, 1355.

Most of the structures featured in Part II of these posts on ancient Mazaka/Caesarea were built after the city had been completely destroyed by the invading Seljuk army under Alp Arslan. Only after the city had been abandoned for over fifty years following this destruction and the massacre of the inhabitants in 1067 by the great grandson of Seljuk, was the city slowly re-inhabited.

The two-storied rectangular building pictured above and below is known as the Emir Ali Pisrev Tomb, because it was constructed (according to inscriptions within the upper chamber) for Emir Ali Pisrev, who died in 1349. It was built during the Eretna period, and was erected after the death of Emir Ali Pisrev. The inscribed marble block above the muqarnas that tops the arch relief reads "Mashhad", written in Arabic thuluth script, which denotes a holy person, or religious pilgrimage site.

What the signage does not inform us of is that, the upper room (the entrance seen here with the brown wooden door) may have also served as a mosque, as there is a mihrab niche opposite the entrance that indicates the direction of Mecca. There are three windows in the upper room, on the west, south, and east walls. The burial tomb is located under the upper chamber, the entrance to which can be seen in the photo above, under the double-staircase, through the blue door. Apparently, no bodies remain within the tomb.

As you can see in the two photos above, the new and old signs at the site of the Kutlug Han Tomb have differing dates for its construction, 1349 versus 1350, while a cenotaph at the site states 1343. What's a year or two (or a few more) in the scheme of things? Well, to some absolutely nothing, while to others, everything. The tomb consists of two parts, a square section with a dome roof, and an oblong square section with a pyramidal roof, which was meticulously reconstructed from cut stone in 1977.

I have to say, that Kayseri city has put an enormous amount of effort into the restoration of its historical monuments, as every ancient tomb, madrasa, mosque and church that I visited had seen some level of restoration. At the end of this post, you will see that this reconstruction work even includes historic 19C structures and whole areas that had long been abandoned and left to squatters, or allowed to collapse.

Regardless, a marble plaque above the muqarnas states that the tomb (or, mausoleum) was built in 1350 by Sah Kutlug Hatun for his/her two sons Emir Bahsayis and Emir Haydar Bey. Some assume that the Sah himself/herself would also have been interred within the tomb. I am using "his/her", and himself/herself", because not only is the signage at the site confusing, but, it's difficult to access open information online. I would assume that Sah Kutlug Hatun was male (read the English sign closely).

The elaborately decorated tomb was built during the Eretna Beylik period, which was discussed at length above. Shortly after this tomb was completed, the Ottomans began to make their expansion eastward.

The Sah Kutlu Han tomb was restored in 1977, and again received further attention in 1992 to 1993. The crown door and its portal are stone work sculpted during the Late-Seljuk period, and, is an imitation of the preceding Ilhani style.

When viewing the magnificent geometric designs and floral reliefs in such an artistic display, one can understand why there was such a resurgence of the Middle-Eastern and Asia Minor architectural style during the early to mid-20th century in cities across the U.S. My hometown Detroit is a bastion of this style, though many of the buildings are slowly being lost to urban decay.

Perhaps in a more prosperous future, the cities of the U.S. will follow the lead of Kayseri, and understand that, one of the most important things a city can offer is the rich architectural past. Once these monuments and structures are destroyed, their physical majesty is lost to all future generations.

Unfortunately, when I was taking my whirlwind bike tour to antiquities around the city, I had no idea that this little mausoleum is actually serving as an extension to the Kayseri Archeological Museum. Though on this particular day the museum was closed, it offers a display of stone fragments and sculptures.

The inscription on the marble plaque secured above the entrance reads, This is the tomb Emir Mehmed, son of Zengi." This inscription dates the construction of the tomb to the Eratna period. This structure has also been restored.

Throw a stone in Kayseri, and it will hit a tomb, madrasa, Roman monument, or cat. Located in the Yanikoglu District, pictured here is the Sahap Tomb, which the inscription states was constructed from 1327-1328. There are three burials inside, one being for Emir Sahap, and the others for his relatives.

Further information on Emir Sahap himself would require a deep dive into academic texts written in languages other than English, so, we'll wait for the advent of GPT application!

Also located in the Yanikoglu District, and not far from the Emir Sahap Tomb, is the Babuk Bey Zaviyesi. Interestingly, 'zaviyesi' translates into 'lodges, or, mansion'. Though the information board on the structure reads "1336", it was actually constructed in 1366-1367.

What might be shocking for modern inhabitants of Kayseri (and greater Turkey), and myself upon discovery, is that this structure was built by the son of a martyred member of the Mongolian army. The martyred Mongolian was Toga Timur, who was killed here in Kayseri. Later, as a member of the Mongolian occupying army, his son Haci Babuk came to Kayseri, stayed, and built this tomb.

The inscription on the structure reads, "The great sultan, the ruler of nations, the son of Toga Timur, Haci Babuk, ordered the construction of this blessed building, Muharrem h.768 (1366), so that his property would be permanent." I did see a similar tomb structure like this in Malatya (Melitene), with its square facade over an open-end arched room, though the one in Melitene was not restored.

Here in front of the Sahabiye Madrasa is where the front brake pad of my bike popped out and began scratching the surface of the brake disc. Wouldn't you know it, this was one of the rare times I was caught off guard without my tool kit. Never again.

As for the madrasa, it is stunning, with ornate relief work, yet sparingly restored without some of the finer relief included. 'Madrasah' is an Arabic word, which translates to English as 'educational institution'. I guess, for some, education means a lack of questioning. I do not consider indoctrination to be education, though it can serve the purpose of building a team/side/tribe/etc. As I guess we suspect, all teams/sides/tribes/etc., most often discover an opponent, no?

Also in Pt.1, we looked at some aspects of the Haci Kilic Madrasa (pictured below), only because the stone blocks used to construct the main building in 1249 (not the minarets, constructed in 1547) obviously come from the ruins of previous Roman and Byzantine structures.

If you look closely at the photos above and below, stone architrave blocks, along with other early building members from the Roman and Byzantine periods can be seen. The odd shaped blocks that make up the rest of the building are obviously quarried from other structures.

The Haci Kilic Madrasa was constructed under the direction of Ebu'l-Kasim Bin Ali Tusi in 1249, during the late-Seljuk period. Without going into extensive detail regarding the ornate stone relief surrounding the entrances, let's just say that the geometric images are some of the most elaborate examples to be seen in the city.

The white colored stone belt under the niche (pictured above and below), is the 18th verse of Sarah At-Tawba, and is written in Jali Thuluth.

It reads,"Only those who believe in Allah and the Last Day, perform the prayers, pay zakat and fear no one but Allah, can build the mosques of Allah. These are the ones who hope to be among the righteous."

I had originally planned to photoshop the three photos you see here (above and below) together into one tall photo, but I'm already three years behind on my blog, and I've spent the entire winter on my boat in Izmir trying to get caught up.

This is an exhausting exercise, however, when I'm going back through these pictures, I get a euphoric stimulation that can't be described. I plan to cycle again during the summer of 2023, and not sail, which should say something about how much I love tour cycling.

The burial tomb next to the square based minaret was constructed in 1552, and belonged to Hüseyin Bey (pictured above). However, if you notice, the tomb structure is missing, and all that remains is its large square base, which the sarcophagus and tombstones are sitting on. The tomb was moved inside the mosque when the road was widened.

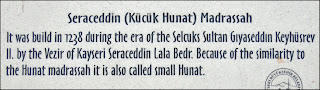

I was really surprised to see the Seraceddin Madrasa turned into cafe! Don't get me wrong, I'm ok with it being re-purposed, however, I would have thought the city would never allow such commercialization of an antiquity. Actually, I'm not so ok with it.

Moving into the 12th century, pictured above and below is the Mesud Gulzar Tomb, which was constructed in 1186 during the Seljuk Period (my bicycle can be seen leaning against the bench). I wish I could say I visited all of the post Byzantine period structures around the city, because in writing this post, I am gaining a greater appreciation for them.

In the past, I almost always bypassed any structure built after the Byzantine period, unless there were more ancient building blocks incorporated into the structure. As for the structures I missed in Kayseri, I am pleased to announce a future return to the Kayseri region for more touring cycling, and I will definitely explore the post-Byzantine buildings I missed the first time around.

The Alaca Tomb (pictured above, and in the left of photo below), takes us back to remains of the Byzantine city, the blocks from which this tomb was likely constructed. Though the tomb information sign states 13th century, the tomb was actually built in 1184, across from what remains today, and had remained of the Byzantine Walls at Yoghanburc (pictured in the distance below) following their destruction in 1067. Following the destruction in 1067, the city was not re-inhabited for another 50 years, until 1117.

Alaca Tomb is an octagonal structure with a cone-shaped roof. The door of the tomb (pictured below) faces north, and is flanked by two windows (sorry I did not get a better photo of the door!). What's left of the inscription on the epitaph for the tomb reads,"This tomb belongs to the late Emir Sadreddin Omar bin Jamaleddin Muhammad."

The Alaca Tomb did serve as a mosque at some point, and considering it's early date of construction, and it's location in the center of the ancient city, the building probably stood out amongst the rubble of the ruined Byzantine capital. Pictured below, Alaca Tomb, with a Byzantine wall rising in the distance.

Though most tourist get little time to explore the ancient buildings and archeological museum in Kayseri, there are hidden gems around every corner, and those magnificent fortress walls do beckon.

Please be sure to check out Caesarea Mazaka Pt.1, where I explore the more ancient ruins of the city, such as the Roman bath complex, the Roman tomb, the Archeological Museum, and so on.

We'll end the post with some magnificent 19C AD Neo-Classical buildings that are located in a rundown part of Kayseri, but which are undergoing a massive area-wide restoration project aimed at preserving these gems.

One of the most facinating areas in Kayseri is an old section between Bestepeler, which is a large hill with an ancient tumulus on top, and the city center. I had just come from Bestepeler, the whether was turning bad, and the sun was going down, so I snapped as many photos as I could. Pictured above and below, the same Neo-classical house photographed twice, one with flash, and one without.

The area is scarcly populated with squatters of various backgrounds, some legitimate landowners, and some businesses. The architecture is what stands out, as well as the city's restoration works aimed at saving what is still standing. Pictured below, one of the many sign-boards with information on the structure being restored.

As you see above and below, the city ('belediye', in Turkish) has created information posters explaining the restoration works, and hung them around the buildings they are working on. Many of these posters show architectural diagrams/blueprints, the cost of the restoration, and so on.

During the 19th century, this was one of the most prosperous neighborhoods in the city, as this build can attest. Notice the bifurcated staircase rising above the carriage house doors and stables (pictured above and below).

You can see the house circled in red on the poster below, with Bestepeler in the distance. The poster also shows how many of these gems have been lost.

Pictured below is another of these gems, though I'm not sure if it was under restoration when I took this photo in 2017. The build is surrounded by a protective barrier, and there was a police car standing nearby, though I think that was for me. The area was quite sketchy, and seemed a bit unsafe at night.

The facade of this mansion is lovely, and again, the residence is located above the carriage house and horse stables. I will certainly make this area a point of destination upon my return to Kayseri, so that I can see what progress has been made.

I thought the building pictured below was quite interesting, because I can't understand why it has such an arch?! Is the arch protecting what used to be the carriage house and stables? I don't think so.

So, was this a tomb, a mosque, or perhaps a church? The arched door in the foreground of the photo, with its Neo-classical frame, is also interesting (bottom left corner in the photo above, and in the right of the photo below). Regardless, it had occupants, and was blocked off from entering. I guess it's not on the restoration list . . . , yet.

The number of Neo-classical structures to be found in this area astounds, because they linger around every corner. These structures were built in a classical style using the same traditional building materials as the ancient tombs, madrasas, mosques and churches found all around the city.

It's obvious that they are valued and have gained the attention of the city. You see the wooden support beams that have been put in place along the side wall of the building (picture above and below) in an attempt to keep the wall from collapsing until further rescue can arrive.

Pictured below, restoration works in progress and nearing completion. This street is being completely rejuvenated. All I can say is, they are building it, and I hope the people come, because I found the effort truly joyful.

I know it's hard to fathom, but instead of going to the beach or Cappadocia for two weeks, spend some days in Kayseri, because they are trying very hard!

These photos were taken in 2017, and some shops and restaurants were open then, so now this street must be hopping! Well, it's Kayseri, I know, but just look at these Ottoman era buildings on this street. It's a walk back through time!

Pictured below, yet another Neo-classical building on support, literally. I was trying to find my way back to the Oretmenevi (Teacher House), because it was getting dark, but these beautiful building kept popping out of nowhere.

Again, solid stone blocks, Neo-classical design, decorative iron frame around the entrance, and ribbon relief in the stone arch. This building looks like there may have been repair work at some point in its past, but now it requires life saving support.

Just as an interesting reference, the 2-3C CE Roman Tomb pictured below is not far from these 19C CE Neo-classical structures, and I have written about it in Caesarea Mazaka Pt.1, but look and compare the style of the tomb and the buildings above, and you will see a direct lineage.

*All photos and content property of Jack A. Waldron (photos may not be used without written permission)

**If you'd like to help with future postings, please feel free to support them through PATREON: