Photos by Jack A. Waldron

The photo above was taken as I was leaving Konya (37°52'04.3"N 32°29'37.4"E). I'm pointing at this koleji building because I wanted do some research for a possible teaching position. Konya is not the most popular tourist destination, or for living, but I find the changing landscapes very magical, and the antiquities are spectacular, of course.

The öğretmenevi (teacher house) in Konya was full, so I had to find the cheapest little back alley hotel with a vacancy. You have to love the silky red bed cover and the cheap pressed wood furniture in my accommodation (pictured above). I had to walk twenty minutes to find a beer shop, and that too was located in some back alley. There's a reason many people wish to avoid Konya, but I was there for the Konya Archeological Museum (37°52'04.3"N 32°29'37.4"E), and to report the vandalism of antiquities at ancient Kilistra.

Back at Catalhoyuk (37°39'56.9"N 32°49'38.2"E), I made my way from the massive dome of the East Mound over to an older southern section of the ancient city that, was built up the slope of the East Mound (pictured above and below). As you will see, Catalhoyuk was under heavy excavation while I was there. When it comes to the history of human settlement, this is one of the most important sites in the world. In the photo below, you see the ongoing excavations of the top of the southern slope of the East Mound. If you look in the center left of the photo, you can see the protective roof covering the southern slope.

When we look at the photo above, it's very challenging to get an image in ones mind of what was once here. In order to help both visitors and archeologists get a better idea of the structures at this site, they have re-created some buildings for this purpose (pictured below).

It must be remembered that these buildings were not free standing, and that residences had shared walls, and the community largely carried out life on the roofs of these dwellings.

The open doors you see in the walls of the re-created house would have led to other rooms. The dwellings were accessed by ladders from the roofs.

When I look at these dwellings, structures, spaces, I see caves, and buildings such as these seem like an obvious progression from shelters that were common in earlier human lives, that being, the cave. My hypothosis is that, for a growing population there just weren't enough caves to go around, and certainly not in the same location, which would have been needed for extended family members. So, the next step was to carve out caves from soft volcanic tuff, such as those found all around Turkey, and these communities expanded more and more.

One problem that comes with carving dwellings out of soft stone is, the best areas of land for living didn't always have tuff or soft stone available, but if we build our cave we can then build them somewhere we like. Further, the defensive aspect of these communities is somewhat similar to the underground cities we find in Cappadocia, and beyond. Catalhoyuk is essentially an underground city. One question I have with regard to the defensive nature of these dwellings is, was there a mechanism to block forced entry through the roof entrance hole?

It has been written that Catalhoyuk shows no signs of having been attacked or laid under siege. We know that the doorways into the caves of Cappadocia were defended by being blocked with massive rolling stone slabs. Was there little or no large clan warfare in the beginning of human settlement? Did larger conflicts between clans or tribes only occur later in human existence as more and more competition for space arouse?

Pictured below, a view up the southern slope of the East Mound. Unfortunately, visitors are not allowed to enter the areas under excavation, so it was impossible for me to get photos of the wall paintings, which we will discuss further below in this post.

Basically, the photo above and the illustrated plan below are looking at the same area. Number 1 shows the last evidence of ancient activity at Catalhoyuk (around 5900 BCE), and that is up at the top of the slope, just above the space/dwelling where you can see two archeologists (one in a blue baseball T-shirt) working on some restoration, and who are featured further down in this post. Number 2 is out of the photo off to the right, and is where a plastered human skull was found. Number 3 is out of the photo to the left, and is the location of the famous wall painting that is possibly depicting an erupting volcano.

Number 4 is located at the bottom center right, and is the location of the vulture paintings, now covered and protected by wooden walls, and held in place with beams crossing over the pit. Number 5 is located a bit further down in the pit, and is where the earliest pottery has been unearthed at the site thus far, dating to around 7000 BCE. Finally, Number 6 is located at the very bottom of this pit, and holds the earliest evidence of occupation at the site, dating to around 7250 BCE. The illustration on the site signboard (pictured below) helps us see how the southern slope once looked.

The re-created mud bricks seen in the photo below have been sun-dried, and are being secured in place using a mortar made from either lime or clay. The archeologists are using the same techniques and materials to complete the re-construction of these dwellings.

You can see a large dark patch of wet mud on the wall in the right of the photo above (and a close up in the photo below), which I imagine was used to restore and protect a damaged section of the wall.

After curing, the mud will be covered with layers of plaster. Over the life of such walls, layers of plaster were added once or twice a year, and this continued until the space was abandoned.

Some of the reasons for piecing back together some of the structures is to both preserve them, and to help us understand how these spaces functioned.

I'm sure that when all this work is completed, guided tours will be provided, and visitors will be ushered through these rooms and dwellings.

Something I had really hoped to see were the various original wall paintings at the sight. When I visited Aslantepe in Malatya, a site with a very similar story and age, I was able to photograph some of the original wall paintings. You can see them in Part 3 of my posts on Aslantepe.

Another similarity with Aslantepe, are sculpted wall patterns, though of course they are from different periods, there may be some ancestral relationship. Some of these sculpted wall designs from Catalhoyuk are on display at the Konya Archaeological Museum.

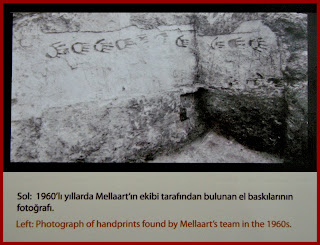

Handprint paintings have been a go to design for humans over tens or thousands of years. Pictured below, this is a photo of some wall handprints in situ at the Catalhoyuk site.

Pictured above and below, these are my photos of some handprint paintings from Catalhoyuk that have been excavated, extracted and put on display at the Konya Archeological Museum.

The most interesting aspect about these handprint paintings is that they do not appear to be prints made by pressing a hand covered in paint against a wall, but are paintings of hands, or, of handprints.

Children often paint on their bedroom walls (and occasionally beyond), and it is sort of a right of passage. These children are sometimes congratulated for your accomplishments, or as in my case, yelled at and spanked.

I suppose painting on walls has always been held in some regard for both children and adults, but how was the wall art regarded at Catalhoyuk thousands of years ago?

I wonder, at Catalhoyuk, did children dare to touch those walls with a brush or a burnt stick, or, were those canvases reserved for something greater, beyond human, perhaps like the sculptures on the T-pillars at Gobekli Tepe?

Pictured above, 'Painting of a Red Bull', which is one of the more common motifs at the site, along with other artistically represented beasts. Pictured below, some geometric design painting, which is also found widely at Catalhoyuk.

In my paintings (one example pictured below, Title: Pigment Spot by Jack A. Waldron), I use a lot of geometric designs that come to me naturally, and since I am not a trained painter, I wonder if geometric images are innate in the human psyche.

Pictured below, Catalhoyuk wall painting fragment 'Unit 4223.X.1', which was found in 'Building 2, Space 117' at 'Level IX' in 1999.

Just to give the reader an idea of the sizes of these rooms, 'Unit 4223.X.1, Building 2, Space 117, Level IX' is illustrated below, and you can see in the key the length of '5 meters' is given.

On the far left, just outside the edge of the photo below, is a well known painting referred to as the 'Volcano Painting'. This painting was covered, so I couldn't really locate it. To tell the truth, everything was quite difficult to locate, and I was a bit overwhelmed by the site, because to the day visitor, it all looks like a big jumbled organized mess.

As far as I could tell, absolutely all of the paintings were/are under covered protection from the elements, and especially from the sunlight, which is something I learned from my visit to Aslantepe. At Aslantepe, the wall paintings are only open at certain times of day in order to protect them from the sun.

Though the original paintings at the site are not open for display, there are reproductions on site, such as the one pictured below.

This reproduction of the so-called 'Volcano Painting' can be viewed at the site of excavation, and a second reproduction can be seen within the re-created dwelling near the entrance gate to the site (viewed on the right wall in the photo below).

Also, there is a reproduction of the 'Vulture Painting', that can be viewed within the same re-created dwelling near the entrance gate, and that painting is showcased further down in this post.

First, let's take a look at the so-called 'Volcano Painting' (illustrated above). When I look at this painting and, have in mind 'Volcano Painting', I automatically conjure up Mount Karadag, the now extinct volcano some 45 kilometers to the southeast of Catalhoyuk. If you are interested in that area and Mount Karadag, please read my two posts on ancient Barata (aka. Binbir Kilise), Part 1 and Part 2.

However, the information signboard pictured above points the finger at an extinct volcano some 100 kilometers to the northeast by the name of Mount Hasan Dag, though there is no explanation of how this conclusion was arrived at.

The only idea I can come up with as to why they think the so-called 'Volcano Painting' is depicting Mount Hasan Dag (btw, 'Dag' in Turkish means 'mountain'), is that the rectangular images may represent the dwellings at Catalhoyuk, and the so-called mountain is set above settlement, to the north.

Another interpretation of the so-called 'Volcano Painting', is that it represents a stretched out animal skin. Moving on, the upper right wall (could be the lower right wall?) in the photo above (covered with wooded paneling), is (I think), the location of a famous group of wall paintings referred to as the 'Vulture Paintings' (re-created below).

The paint used to create these works of art is red ochre, which is made from a variety of iron oxide known as hematite. Through the process of roasting limonite, it becomes redder and redder the longer it is roasted, until it finally becomes burnt, or, burnt sienna.

Similar to so many ancient works of art, wild beast motifs are an omnipresent fixture in the lives of the people who lived so close or within nature and natural surroundings. Whether boars, snakes, or scorpions for the builders of Gobekli Tepe, or, lions, leopards and griffins for the Phrygians, or, wolves, eagles and bulls for the Romans, nature was intertwined with daily life during those time periods.

However, as the centuries moved forward, and nature became more and more distant, the connection with nature lessoned, a bit less for imperial Romans as they were centered in their cities, and progressively until the current world of today, a virtual reality of nature for most.

Another close connection for the inhabitants of Catalhoyuk, were the dead, who were buried beneath the floors and platforms within the dwellings, with the occupant family members sleeping above them.

Pictured below, a photo from a display at the site shows a platform within a dwelling that has a burial chamber beneath it. During occupancy, the inhabitants would have laid a reed mat over the platform, and used the space for relaxing, sleeping, and various other activities.

Perhaps there was the belief, that burial of the dead beneath the platform you slept on would enhance fertility? Or, maybe the wisdom of the dead would be kept close-at-hand, and in the minds of the living?

Archeologists at Catalhoyuk have found burials beneath dwelling floors or platforms with up to sixty individuals. That said, not every dwelling was used for burials, and numbers of individuals within the burial chambers ranges from three to sixty, so what was the reason?

As it appears to us now, when a family member from a household passed, and a new burial was to be performed, a space of significance was chosen for reasons we don't know, a floor or platform tomb was opened or built upon, or expanded, and the burial took place. Perhaps there was some relatedness between the dwelling renewal process, that was discussed in Catalhoyuk, Part 1, and the burial ritual?

The bodies of the dead were laid in the crouch position, and usually with some items. There are many information boards at the site and at the Konya Archeological Museum that help explain the burials, as well as the excavation process.

The number 4 'Baby with Beads' burial is illustrated below, and the most significant aspect of this particular burial are the beaded bracelets that were found with the baby.

Pictured below, my photo of the 'Baby with Beads', which is on display at the Konya Archeological Museum. You can see the beaded bracelets on both arms of the baby, however, the teardrop beads of the ankle bracelets are a bit harder to discern.

The museum provided the photo below, and here, the ankle bracelets with their teardrop beads are much easier to see. The material of the beads, is either clay, stone, or shell, though I didn't see mention of what the baby bracelets used. We will take a look at stone drilling tools for beads and other materials further down in the post.

Pictured below, another of my photos of the 'Baby with Beads' burial. I can imagine the mother and father sleeping above their deceased baby, and renewing their bond and love, daily.

Pictured below, a museum photo of grave beads found at Catalhoyuk. Further below, a close-up photo of some grave beads from Catalhoyuk on display at the Konya Archeological Museum.

Pictured below, a necklace with teardrop beads that was found in a grave at Catalhoyuk.

Pictured below, I believe this is a pendant, but the museum information tab says 'bendant'. I think they made a mistake, but I can't be sure.

Pictured below, these are drills made from bone, and they would have been used to drill holes in hardened clay beads, leather, wood, and so on.

Pictured below, this is a stone drill sharpener from the Neolithic period that was found at Catalhoyuk.

Pictured below, these are stone mirrors from the Neolithic period, and were also found within graves at Catalhohuk.

At the Konya Archeological Museum, one of the most unique burials found at Catalhoyuk is on display, titled, 'Plastered Human Skull and Jawbone'.

It was found in 2004 in Building 42, which is at level V, and is dated to around 6300 BCE. Pictured below is my photo of the 'Plastered Human Skull and Jawbone' burial, which is on display at the Konya Archeological Museum.

"This human skull and jawbone is unique among the human remains excavated at Çatalhöyük. It was excavated in 2004 from a burial in Building 42 [F.1517], a building currently dated to Level V, approximately 6300 BC. The skull and jawbone are covered in soft white plaster that has then been painted with a dark red paint. The plaster extends from the forehead to the chin; the red paint from a little further up the forehead all the way across the plaster. The eye-sockets have been filled in with plaster, but the top teeth have been left exposed, although they have been painted with red paint. The nose was modeled in plaster. The plaster over the right socket shows traces of more than one layer of plaster and red paint, indicating that the skull and jawbone were replastered and repainted several times. This may perhaps suggest that they were kept on display somewhere prior to being buried in Building 42. The skull and jawbone appear to have belonged to an adult female."

"This plastered and painted head was positioned in the grave along with a female burial. This body was lying on its left side in a crouched position, a common burial pose at Çatalhöyük. The woman was buried cradling the head against her chest so that her forehead rested against the forehead of the plastered skull. Since there are no other examples of burials such as this at Çatalhöyük, it is unclear what the relationship between the two women was. The burial occurred during the construction of Building 42, and it has been suggested that they were individuals significant to the family or clan who constructed the building. The head may have belonged to an important ancestor. Perhaps her body is buried in an earlier house underneath Building 42.

The only other plastered skulls found in Turkey have come from the site of Köskhöyük. Similar plastered skulls have also been found in the Near East from the Late Neolithic period. The presence of such a plastered skull at Çatalhöyük suggests possible connections between Catalhöyük and these other sites."

*All photos and content property of Jack A. Waldron (photos may not be used without written permission)

**Please support my work and future postings through PATREON:

Or, make a Donation through PayPal: